Full Stack Development Internship Program

- 29k Enrolled Learners

- Weekend/Weekday

- Live Class

In the world of object-oriented programming (OOP), there are many design guidelines, patterns or principles. Five of these principles are usually grouped together and are known by the acronym SOLID. While each of these five principles describes something specific, they overlap as well such that adopting one of them implies or leads to adopting another. In this article we will Understand SOLID Principles in Java.

Robert C. Martin gave five object-oriented design principles, and the acronym “S.O.L.I.D” is used for it. When you use all the principles of S.O.L.I.D in a combined manner, it becomes easier for you to develop software that can be managed easily. The other features of using S.O.L.I.D are:

When you use the principle of S.O.L.I.D in your coding, you start writing the code that is both efficient and effective.

Solid represents five principles of java which are:

In this blog, we will discuss all the five SOLID principles of Java in details.

What does it say?

Robert C. Martin describes it as one class should have only one and only responsibility.

According to the single responsibility principle, there should be only one reason due to which a class has to be changed. It means that a class should have one task to do. This principle is often termed as subjective.

The principle can be well understood with an example. Imagine there is a class which performs following operations.

Connected to a database

Read some data from database tables

Finally, write it to a file.

Have you imagined the scenario? Here the class has multiple reasons to change, and few of them are the modification of file output, new data base adoption. When we are talking about single principle responsibility, we would say, there are too many reasons for the class to change; hence, it doesn’t fit properly in the single responsibility principle.

For example, an Automobile class can start or stop itself but the task of washing it belongs to the CarWash class. In another example, a Book class has properties to store its own name and text. But the task of printing the book must belong to the Book Printer class. The Book Printer class might print to console or another medium but such dependencies are removed from the Book class

When the Single Responsibility Principle is followed, testing is easier. With a single responsibility, the class will have fewer test cases. Less functionality also means fewer dependencies to other classes. It leads to better code organization since smaller and well-purposed classes are easier to search.

An example to clarify this principle:

Suppose you are asked to implement a UserSetting service wherein the user can change the settings but before that the user has to be authenticated. One way to implement this would be:

public class UserSettingService

{

public void changeEmail(User user)

{

if(checkAccess(user))

{

//Grant option to change

}

}

public boolean checkAccess(User user)

{

//Verify if the user is valid.

}

}All looks good until you would want to reuse the checkAccess code at some other place OR you want to make changes to the way checkAccess is being done. In all 2 cases you would end up changing the same class and in the first case you would have to use UserSettingService to check for access as well.

One way to correct this is to decompose the UserSettingService into UserSettingService and SecurityService. And move the checkAccess code into SecurityService.

public class UserSettingService

{

public void changeEmail(User user)

{

if(SecurityService.checkAccess(user))

{

//Grant option to change

}

}

}

public class SecurityService

{

public static boolean checkAccess(User user)

{

//check the access.

}

}Robert C. Martin describes it as Software components should be open for extension, but closed for modification.

To be precise, according to this principle, a class should be written in such a manner that it performs its job flawlessly without the assumption that people in the future will simply come and change it. Hence, the class should remain closed for modification, but it should have the option to get extended. Ways of extending the class include:

Inheriting from the class

Overwriting the required behaviors from the class

Extending certain behaviors of the class

An excellent example of open-closed principle can be understood with the help of browsers. Do you remember installing extensions in your chrome browser?

Basic function of the chrome browser is to surf different sites. Do you want to check grammar when you are writing an email using chrome browser?If yes, you can simply use Grammarly extension, it provides you grammar check on the content.

This mechanism where you are adding things for increasing the functionality of the browser is an extension. Hence, the browser is a perfect example of functionality that is open for extension but is closed for modification. In simple words, you can enhance the functionality by adding/installing plugins on your browser, but cannot build anything new.

OCP is important since classes may come to us through third-party libraries. We should be able to extend those classes without worrying if those base classes can support our extensions. But inheritance may lead to subclasses which depend on base class implementation. To avoid this, use of interfaces is recommended. This additional abstraction leads to loose coupling.

Lets say we need to calculate areas of various shapes. We start with creating a class for our first shape Rectangle which has 2 attributes length & width.

public class Rectangle

{

public double length;

public double width;

}

Next we create a class to calculate the area of this Rectangle which has a method calculateRectangleArea which takes the Rectangle as an input parameter and calculates its area.

public class AreaCalculator

{

public double calculateRectangleArea(Rectangle rectangle)

{

return rectangle.length *rectangle.width;

}

}So far so good. Now let’s say we get our second shape circle. So we promptly create a new class Circle with a single attribute radius.

public class Circle

{

public double radius;

}Then we modify Areacalculator class to add circle calculations through a new method calculateCircleaArea()

public class AreaCalculator

{

public double calculateRectangleArea(Rectangle rectangle)

{

return rectangle.length *rectangle.width;

}

public double calculateCircleArea(Circle circle)

{

return (22/7)*circle.radius*circle.radius;

}

}However, note that there were flaws in the way we designed our solution above.

Lets say we have a new shape pentagon. In that case, we will again end up modifying the AreaCalculator class. As the types of shapes grows this becomes messier as AreaCalculator keeps on changing and any consumers of this class will have to keep on updating their libraries which contain AreaCalculator. As a result, AreaCalculator class will not be baselined(finalized) with surety as every time a new shape comes it will be modified. So, this design is not closed for modification.

AreaCalculator will need to keep on adding their computation logic in newer methods. We are not really expanding the scope of shapes; rather we are simply doing piece-meal(bit-by-bit) solution for every shape that is added.

Modification of above design to comply with opened/closed principle:

Let us now see a more elegant design which solves the flaws in the above design by adhering to the Open/Closed Principle. We will first of all make the design extensible. For this we need to first define a base type Shape and have Circle & Rectangle implement Shape interface.

public interface Shape

{

public double calculateArea();

}

public class Rectangle implements Shape

{

double length;

double width;

public double calculateArea()

{

return length * width;

}

}

public class Circle implements Shape

{

public double radius;

public double calculateArea()

{

return (22/7)*radius*radius;

}

}There is a base interface Shape. All shapes now implement the base interface Shape. Shape interface has an abstract method calculateArea(). Both circle & rectangle provide their own overridden implementation of calculateArea() method using their own attributes.

We have brought in a degree of extensibility as shapes are now an instance of Shape interfaces. This allows us to use Shape instead of individual classes

The last point above mentioned consumer of these shapes. In our case, the consumer will be the AreaCalculator class which would now look like this.

public class AreaCalculator

{

public double calculateShapeArea(Shape shape)

{

return shape.calculateArea();

}

}This AreaCalculator class now fully removes our design flaws noted above and gives a clean solution which adheres to the Open-Closed Principle. Let’s move on with other SOLID Principles in Java

Robert C. Martin describes it as Derived types must be completely substitutable for their base types.

Liskov substitution principle assumes q(x) to be a property, provable about entities of x which belongs to type T. Now, according to this principle, the q (y) should be now provable for objects y that belongs to type S, and the S is actually a sub type of T. Are you now confused and don’t know what Liskov substitution principle actually mean? The definition of it might be a bit complex, but in fact, it is quite easy. The only thing is that every subclass or derived class should be substitutable for their parent or base class.

You can say that it is a unique object-oriented principle. The principle can further be simplified by ; a child type of a particular parent type without making any complication or blowing things up should have the ability to stand in for that parent.This principle is closely related to Liskov Substitution principle.

This avoids misusing inheritance. It helps us conform to the “is-a” relationship.We can also say that subclasses must fulfill a contract defined by the base class. In this sense, it’s related to Design by Contract that was first described by Bertrand Meyer. For example, it’s tempting to say that a circle is a type of ellipse but circles don’t have two foci or major/minor axes.

The LSP is popularly explained using the square and rectangle example. if we assume an ISA relationship between Square and Rectangle. Thus, we call “Square is a Rectangle.” The code below represents the relationship.

public class Rectangle

{

private int length;

private int breadth;

public int getLength()

{

return length;

}

public void setLength(int length)

{

this.length = length;

}

public int getBreadth()

{

return breadth;

}

public void setBreadth(int breadth)

{

this.breadth = breadth;

}

public int getArea()

{

return this.length * this.breadth;

}

}Below is the code for Square. Note that Square extends Rectangle.

public class Square extends Rectangle

{

public void setBreadth(int breadth)

{

super.setBreadth(breadth);

super.setLength(breadth);

}

public void setLength(int length)

{

super.setLength(length);

super.setBreadth(length);

}

}In this case, we try to establish an ISA relationship between Square and Rectangle such that calling “Square is a Rectangle” in the below code would start behaving unexpectedly if an instance of Square is passed. An assertion error will be thrown in the case of checking for “Area” and checking for “Breadth,” although the program will terminate as the assertion error is thrown due to the failure of the Area check.

public class LSPDemo

{

public void calculateArea(Rectangle r)

{

r.setBreadth(2);

r.setLength(3);

assert r.getArea() == 6 : printError("area", r);

assert r.getLength() == 3 : printError("length", r);

assert r.getBreadth() == 2 : printError("breadth", r);

}

private String printError(String errorIdentifer, Rectangle r)

{

return "Unexpected value of " + errorIdentifer + " for instance of " + r.getClass().getName();

}

public static void main(String[] args)

{

LSPDemo lsp = new LSPDemo();

// An instance of Rectangle is passed

lsp.calculateArea(new Rectangle());

// An instance of Square is passed

lsp.calculateArea(new Square());

}

}The class demonstrates the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) As per the principle, the functions that use references to the base classes must be able to use objects of derived class without knowing it.

Thus, in the example shown below, the function calculateArea which uses the reference of “Rectangle” should be able to use the objects of derived class such as Square and fulfill the requirement posed by Rectangle definition. One should note that as per the definition of Rectangle, following must always hold true given the data below:

In case, we try to establish ISA relationship between Square and Rectangle such that we call “Square is a Rectangle”, above code would start behaving unexpectedly if an instance of Square is passed Assertion error will be thrown in case of check for area and check for breadth, although the program will terminate as the assertion error is thrown due to failure of Area check.

The Square class does not need methods like setBreadth or setLength. The LSPDemo class would need to know the details of derived classes of Rectangle (such as Square) to code appropriately to avoid throwing error. The change in the existing code breaks the open-closed principle in the first place.

Robert C. Martin describes it as clients should not be forced to implement unnecessary methods which they will not use.

According to Interface segregation principle a client, no matter what should never be forced to implement an interface that it does not use or the client should never be obliged to depend on any method, which is not used by them.So basically, the interface segregation principles as you prefer the interfaces, which are small but client specific instead of monolithic and bigger interface.In short, it would be bad for you to force the client to depend on a certain thing, which they don’t need.

For example, a single logging interface for writing and reading logs is useful for a database but not for a console. Reading logs make no sense for a console logger. Moving on with this SOLID Principles in Java article.

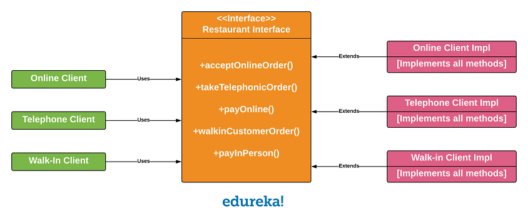

Let us say that there is a Restaurant interface which contains methods for accepting orders from online customers, dial-in or telephone customers and walk-in customers. It also contains methods for handling online payments (for online customers) and in-person payments (for walk-in customers as well as telephone customers when their order is delivered at home).

Now let us create a Java Interface for Restaurant and name it as RestaurantInterface.java.

public interface RestaurantInterface

{

public void acceptOnlineOrder();

public void takeTelephoneOrder();

public void payOnline();

public void walkInCustomerOrder();

public void payInPerson();

}There are 5 methods defined in RestaurantInterface which are for accepting online order, taking telephonic order, accepting orders from a walk-in customer, accepting online payment and accepting payment in person.

Let us start by implementing the RestaurantInterface for online customers as OnlineClientImpl.java

public class OnlineClientImpl implements RestaurantInterface

{

public void acceptOnlineOrder()

{

//logic for placing online order

}

public void takeTelephoneOrder()

{

//Not Applicable for Online Order

throw new UnsupportedOperationException();

}

public void payOnline()

{

//logic for paying online

}

public void walkInCustomerOrder()

{

//Not Applicable for Online Order

throw new UnsupportedOperationException();

}

public void payInPerson() {

//Not Applicable for Online Order

throw new UnsupportedOperationException();

}

}Since the above code(OnlineClientImpl.java) is for online orders, throw UnsupportedOperationException.

Online, telephonic and walk-in clients use the RestaurantInterface implementation specific to each of them.

The implementation classes for Telephonic client and Walk-in client will have unsupported methods.

Since the 5 methods are part of the RestaurantInterface, the implementation classes have to implement all 5 of them.

The methods that each of the implementation classes throw UnsupportedOperationException. As you can clearly see – implementing all methods is inefficient.

Any change in any of the methods of the RestaurantInterface will be propagated to all implementation classes. Maintenance of code then starts becoming really cumbersome and regression effects of changes will keep increasing.

RestaurantInterface.java breaks Single Responsibility Principle because the logic for payments as well as that for order placement is grouped together in a single interface.

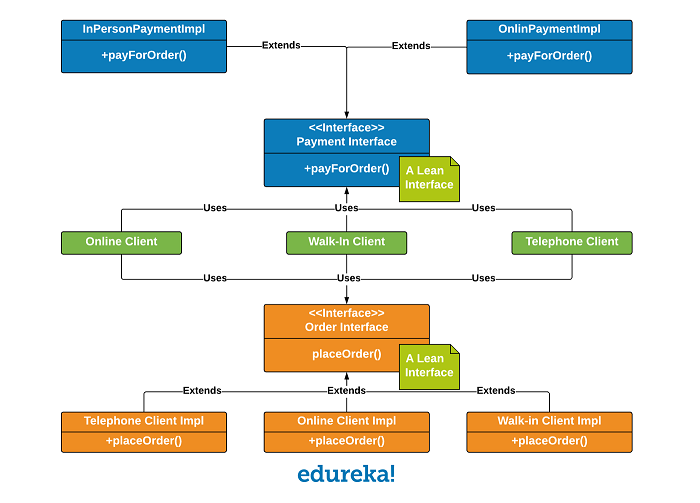

To overcome the above mentioned problems , we apply Interface Segregation Principle to refactor the above design.

Separate out payment and order placement functionalities into two separate lean interfaces,PaymentInterface.java and OrderInterface.java.

Each of the clients use one implementation each of PaymentInterface and OrderInterface. For example – OnlineClient.java uses OnlinePaymentImpl and OnlineOrderImpl and so on.

Single Responsibility Principle is now attached as Payment interface(PaymentInterface.java) and Ordering interface(OrderInterface).

Change in any one of the order or payment interfaces does not affect the other. They are independent now.There will be no need to do any dummy implementation or throw an UnsupportedOperationException as each interface has only methods it will always use.

After applying ISP

Robert C. Martin describes it as it depends on abstractions not on concretions.According to it, the high-level module must never rely on any low-level module . for example

You go to a local store to buy something, and you decide to pay for it by using your debit card. So, when you give your card to the clerk for making the payment, the clerk doesn’t bother to check what kind of card you have given.

Even if you have given a Visa card, he will not put out a Visa machine for swiping your card. The type of credit card or debit card that you have for paying does not even matter; they will simply swipe it. So, in this example, you can see that both you and the clerk are dependent on the credit card abstraction and you are not worried about the specifics of the card. This is what a dependency inversion principle is.

It allows a programmer to remove hardcoded dependencies so that the application becomes loosely coupled and extendable.

public class Student

{

private Address address;

public Student()

{

address = new Address();

}

}In the above example, Student class requires an Address object and it is responsible for initializing and using the Address object. If Address class is changed in future then we have to make changes in Student class also. This makes the tight coupling between Student and Address objects. We can resolve this problem using the dependency inversion design pattern. i.e. Address object will be implemented independently and will be provided to Student when Student is instantiated by using constructor-based or setter-based dependency inversion.

With this, we come to an end of this SOLID Principles in Java.

Check out the Java Course training by Edureka, a trusted online learning company with a network of more than 250,000 satisfied learners spread across the globe. Edureka’s Java J2EE and SOA training and certification course is designed for students and professionals who want to be a Java Developer. The course is designed to give you a head start into Java programming and train you for both core and advanced Java concepts along with various Java frameworks like Hibernate & Spring.

Got a question for us? Please mention it in the comments section of this “SOLID Principles in Java” blog and we will get back to you as soon as possible.

Thank you for registering Join Edureka Meetup community for 100+ Free Webinars each month JOIN MEETUP GROUP

Thank you for registering Join Edureka Meetup community for 100+ Free Webinars each month JOIN MEETUP GROUPedureka.co